The ABCs of Table Saws

Making Sense of Table Saw Classifications -

Buying a new table saw can be a little confusing to an inexperienced buyer. The models, brands, manufacturers, and types of saws are in a constant state of change. What was true just a few years ago may no longer apply, so it can be difficult to get reliable information even from seasoned veterans if they haven't been keeping up on the trends. Even seasoned veterans may be surprised at how rapidly the marketplace changes. To help simplify your purchase, here's one man's view of the table saw marketplace in the USA (and some Canadian choices) in 2012. Opinions vary widely about which saws are best, and the classifications are more blurred than ever. Because many saws roll off the same assembly lines from the same plant, but sport different name plates and color schemes, in my opinion it's better to focus more on the type of saw that's most suitable for your needs than what brand name to buy. Don't dismiss a full size saw because of your impressions of a portable saw of the same brand, or vice-versa….there's often very little correlation between them. A step up in class from a lesser brand is still a step up in class, and is likely a better choice than a downgrade in class from a more prominent brand. This article will help explain some of the basic features and differences between types of 10" table saws that are commonly found in the US.

The vast majority of table saws available in today's market can be divided into two major categories - portable and stationary, with varying sub-classifications for each. This article will focus only on saws with standard 5/8" arbors that will accept standard 10" saw blades.

Portable Saws:

Portable saws include 3 subgroups - the entry level bench top models, compact saws, and portable jobsite saws. They're primarily designed to be light and mobile. The vast majority have universals motors, most of which are direct drive, and run on standard 120v residential circuits. Those that are belt driven tend to use a light duty cogged vacuum cleaner style drive belt. Universal motors tend to be considerably louder than induction motors, and have less torque, so they tend to rely on higher RPM to get the cutting done. Most have motors that are rated between 10 and 15 amps, and typically generate between 1 and 2 usable horsepower. Claims of greater horsepower than that are misleading…if it plugs into a standard home outlet, it's not more than 2hp (at least not for very long). Many are also available with a variety of lifts and leg stands….which is where our first point of confusion shows up. For the sake of simplicity, let's assume that a portable benchtop or jobsite saw on a leg stand is still a portable saw.

Bench top saws tend to be small, light, inexpensive, and aimed mainly at the entry level casual home owner. There are several models readily available typically costing in the $100-$200 range, or less, from brands like Skil, Black & Decker (Firestorm), Craftsman, Tradesman, Ryobi, Hitachi, Task Force, Rockwell, Central Machinery, Pro Tech, Cummins, Delta, Jet, and others. The same saws mounted on a leg stand can run upwards of $300. To keep weight and cost down, bench top models tend to feature materials and designs that aren't overly robust. Most feature plastic or very lightweight metal housings, plastic or cheap pot metal gears and mechanisms, aluminum or composite tops, very small tables, and poorly designed fences that are awkward and difficult to get accurate results with. Many of these saws are made to "look" the part of higher grade jobsite saw to the uninformed, but the similarities don't go very deep….most are little more than a circular saw mounted upside down in a plastic housing. Many are no more than 17" deep, leaving very little room to operate in front of the blade, which can make safe accurate cuts more difficult. Most don't feature standard size miter slots, or don't accommodate the use of common aftermarket accessories or parts from other saws. Operating space is very limited, and the lighter weight makes them less stable during operation (many weigh in the range of 50#). They'll cut wood and other materials, but can be difficult and frustrating to use. It's often not feasible to repair them in the event of a mechanical or electrical failure. Bench top saws of this type tend to cost less upfront, but generally represent a very poor value overall due to their poor resale value, poor reliability, and mediocre performance. Sometimes it's prudent to save a little longer and spend a little more to spare yourself the trouble and wasted money. Buying a better quality used saw is often a better option if the right deal comes along. In some cases your needs would be better met by a basic circular saw with a good blade, and a decent straight edge used as a guide.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

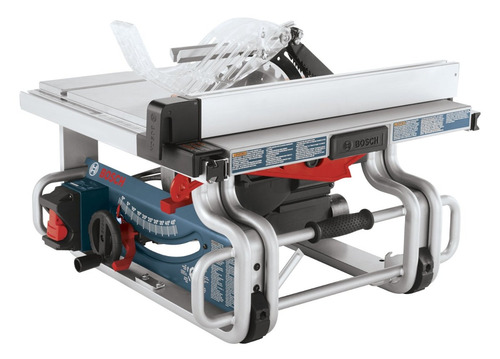

Portable jobsite saws represent a more ruggedly built class of portable saws. These are the type of saws that most carpenters, contractors, and tradesman use on the jobsite… which might explain why they're often incorrectly referred to as "contractor saws". They're still small, light, and portable, and retain many of the disadvantages inherent to a smaller saw, but are made more ruggedly and are generally more accurate than the entry level bench top saws. Most still have direct drive universal motors, and lightweight construction compared to a full size stationary saw, but the motors, gears, and underpinnings are made to hold up better to the rigors and demands of a construction site than most bench top models. Most have reasonably powerful 15 amp motors, many have standard ¾" miter slots, decent fences, better alignment adjustments, extension tables, ripping capacities up to 24", and are available with a variety of clever foldup or rollaway leg stands. There are popular and reasonably capable models from companies like Bosch, DeWalt, Ridgid, Porter Cable, Makita, Jet, Craftsman, Hitachi, and Ryobi, among others. Prices tend to be in the $300-$600 range, and many are capable of suitable accuracy for furniture making in the hands of a skilled woodworker. All have their fans, but the Bosch, DeWalt, and Ridgid are the perennial top dogs in this class. These saws have modern riving knives, some have dust collection ports, and are an excellent option if you need to move the saw easily from location to location, or need to easily stow them out of the way. However, they still don't offer the sheer size, mass, and performance benefits of a full size stationary saw.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

Compact saws are a slightly larger class of saw than the entry level bench models, but are still lighter, smaller, less expensive, and more portable than full size stationary saws. They're often still considered bench top saws, and still tend to retain direct drive universal motors, and less rugged overall construction, though some do feature a cogged vacuum cleaner style belts, and most will have some sort of a leg stand. Some even feature cast iron tops, and can look remarkably similar to a full size contractor saw from a glance, though the table area is smaller and the construction is significant lighter duty.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

Stationary Saws:

Stationary saws include the main categories of contractor saws, hybrid saws, and cabinet saws. They're considerably heavier, larger, and more robust than the class of portable saws. Though inherently less portable, any of these saws can be placed on a mobile base and rolled easily around the shop. Some even have built in mobile bases. These are typically full size saws with cast iron tops and belt drive induction motors, but there are examples that offer solid granite tops instead of cast iron, and even some with aluminum tops. The vast majority have standard ¾" miter slots on each side of the blade. A standard full size top tends to have a main table that's approximately 27" deep x 20" wide, with 10" to 12" extension wings made of steel or cast iron on each side for a total width of roughly 40" to 44". There are exceptions and variations across the board, with some having deeper tables, extra wide extension tables, router tables, outfeed tables, longer fence rails, etc. In a standard configuration, these saws all tend to take up about the same amount of floor space. However, the older style contractor saws with the motor hanging off the back take up an additional 12" to 13" for the motor. It's a common misconception that cabinet saws take up more space. In their stock configuration, the cabinet saws actually have a smaller footprint than a traditional older style contractor saw with an outboard motor. It isn't until you add longer rails for more rip capacity that the area increases for any saw in this class. The misconception arises because it's simply more common to find a cabinet saw with wider rip capacity than it is a contractor saw or hybrid with a similar setup.

This is the class of saw that most hobbyists, smaller professional shops, and schools will gravitate toward. Many will run on a standard single phase 20 amp 120v residential circuit, while others require a 240v circuit (2 horsepower and up). Some that are used in industrial settings will operate on 480v 3-phase circuits. These saws tend to have good adjustability and can be made to be very accurate. They're large and stable enough to handle most sheet goods, powerful enough to cut most lumber to near full blade height if aligned well and fitted with a proper blade. They have ample table space and good operating room in front of the blade, making them inherently safer to use. There are many good fence options available, most will accept standard accessories, and are built to last for decades with basic maintenance. They're also usually easier, and cheaper to fix in the event of a failure. Many of the motors are on a standard NEMA 56 frame, so off-the-shelf replacement and upgrade motors are readily available. Many parts like the wings, fences, and miter gauges are directly interchangeable with all three classes of stationary saws, or can be easily modified to fit, so upgrades for basic features are often possible, making stationary saws a good long term investment.

Compare the significant difference in the size of the "landing zone" in front of the blade between a portable and a full size stationary saw. That extra space not only keeps hands farther away from the blade, it also gives the work piece more time to settle and register against the table and fence providing better accuracy:

![Image]()

.

Contractor Saws:

For years, the most common full size stationary saw has been the traditional contractor saw with a belt drive outboard induction motor hanging out the back of the saw. These were developed over 60 years ago as a jobsite alternative to heavier cabinet saws, and were used by carpenters and craftsman in the field. These were the true original "contractor saws". The motor was designed to be easily removed to improve portability, were initially typically ½ to 1 horsepower, and could run on standard residential 110v circuits (now known as 120v). The belt driven arbor was suspended between two trunnion brackets that mounted to the table top. This design was lighter and cheaper to manufacture, but were a bit difficult to reach and made alignment more of a chore. Over time, the horsepower increased to an average of 1hp to 2hp…about the maximum horsepower rating that a motor that will run on a standard 120v circuit can achieve. Though more portable than a 500# industrial cabinet saw, at 200# to 300#, a traditional contractor saw was still very heavy to be moved regularly from one location to another, but were capable, accurate, and reliable. In addition to being heavy, the location of the outboard motor had some disadvantages….the motor took up more space, required a longer belt (additional vibration), posed a lifting hazard when the motor was tilted, put additional stresses on the alignment when tilted, and generally had poor dust collection. This design remained relatively unchanged for several decades, with most improvements focused on the precision of the fences, safety features like guards and splitters, standardization of table size and miter slots. As smaller, more portable saws evolved, contractor saws became largely relegated to use as permanently located stationary shop saws. They also gained appeal as home shop saws for hobbyists and smaller professional shops because they were more affordable than cabinet saws, yet offered good performance for fine woodworking. In their new role as a stationary saw, easy access for motor removal was no longer necessary, so the location of the motor eventually found its way inside the enclosure, which resolved the nuisance issues of the outboard location. There are very few traditional contractor saws with outboard motors still available new in the marketplace these days. The Saw Stop contractor saw is the sole survivor of currently manufactured consumer table saws with outboard motors. The Powermatic PM64a is still available, but those are all new old stock (NOS)….you may also find some NOS GI and Delta contractor saws at smaller specialty tool stores, but new models haven't been manufactured for a while.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

.

Hybrid Saws:

Most of today's contractor saws feature an inboard belt drive induction motor, as well as an updated splitter known as a riving knife, which raises, lowers, and tilts in unison with the blade as opposed to being fixed in place, or just tilting with the blade as was the case with a traditional splitter. Because the riving knife is less cumbersome, and less likely to be in the way, it's more likely to be in place to do its job. Due to the inboard location of the motor, today's contractor saws are sometimes referred to as hybrid saws, which are a really a cross between a contractor saw and an industrial cabinet saw. One aspect of the older style traditional contractor saws that remains are the open leg or splayed leg enclosures.

There are also several hybrid models that sport full enclosures as opposed to an open or splayed leg stand found on the modern hybrid style contractor saws. Some folks refer to these as cabinet saws, but it's my opinion that it's an oversimplification of the facts. Some savvy marketers promote the confusion by calling their hybrid saws with full enclosures a "cabinet saw". Most of these models still feature table mounted trunnions with similar duty ratings as a contractor saw, but some do offer cabinet mounted trunnions. These are just some of the issues that complicate trying to categorize saw types. I suppose the nomenclature really boils down to semantics, but make no mistake about it….a hybrid saw with a full enclosure, whether it uses table mounted or cabinet mounted trunnions, does not have the same power, mass, duty rating, or robust design as a true industrial style cabinet saw. Modern updated hybrid style contractor saws and hybrid saws are available from companies like Jet, Powermatic, Shop Fox, Ridgid, Craftsman, Delta, Master Force, Craftex, King, Grizzly, Porter Cable, Baleigh, Steel City, General International, Woodtek, Saw Stop, Rikon, Dayton, and others starting at about $525 going up over $2500 for a well appointed Saw Stop model.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

.

.

Industrial Style Cabinet Saws:

Industrial cabinet saws are at the top of the food chain in this article, though there are high volume modern specialty saws available commercially that won't be covered here. Industrial cabinet saws are the true workhorses found in many cabinet shops, factory shops, commercial shops, schools, and serious hobby shops across the country. The vast majority retain the same standard table dimensions mentioned above, so from the top, they can look a great deal like a contractor saw or a hybrid saw. Most can even accept many of the same standard accessories, but aside from that, the similarities under the hood end there. The underpinnings of an industrial cabinet saw are much heavier duty than those of any other type of table saw mentioned here, making them very accurate, heavy, stable, and durable. The fences tend to be precise and robust, often made of heavy welded steel. The mechanisms and adjustments tend to operate as they should, making them a pleasure to use. They also tend to have more horsepower, with most falling into the 3hp to 5hp range, and requiring 240v electrical circuits. There are few standard cuts that these saws struggle with. Most come with a high quality fence, and solid cast iron wings. All of the modern designs that I'm aware of feature cabinet mounted trunnions, which are easier to align than table mounted trunnions. Most have the large yoke style trunnions that span from corner to corner of the cabinet. Weighing in excess of 500# makes these saws very stable, but not very portable. However, when placed on a good mobile base, most can be easily wheeled around the shop. The venerable Delta Unisaw was one of the earliest, most popular, and most copied of this type of saw. There are now excellent examples from Delta, Powermatic, Grizzly, Shop Fox, Jet, Saw Stop, Steel City, Rikon, Laguna, Woodtek, General, General International, Baleigh, Craftex, Oliver, and King Industrial, among others. Starting prices tend to be in the $1300 range, topping out over $4000. Some would consider a saw of this caliber overkill for a hobbyist, but they can be fairly affordable considering what you get for $1300 to $1500 relative to one of the better 120v hybrid saws.

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

![Image]()

Switching a 120v motor to 220v (aka 240v):

Some motors can be run on either 120v or 220v. The benefits of switching to 220v is one of most debated and error ridden discussions you'll find on the internet. My limited knowledge of electricity isn't sufficient to settle all aspects of those debates here, but here's a brief layman's explanation that I hope will at least provide a fighting chance at understanding some of the underlying controversy and benefits involved. (someone please correct me if I've written any glaring errors).

The types of motors used on most saws with induction motors have two sets of coils….they either run in series or in parallel with each other, depending on whether they're wired for 120v or 220v. Each coil sees roughly the same amperage whether run on 120v or 220v, so in theory, there should be no difference in how the motor performs. What changes is the amount of amperage carried by the supply leg or legs of the circuit. The motor is essentially the same, but the supply lines are not, which I think is a key point that often gets overlooked in this debate. 220v circuits supply amperage from two opposite hot supply lines, that each carry half the required current to the motor coils. 120v circuits supply amperage from one hot leg, which supplies all of the required current, which can cause more heat and requires heavier gauge wire. Even though head room is designed into all good electrical circuits, 120v circuits will inherently run closer to 100% of their capacity than a 220v circuit, which can cause some loss of efficiency and voltage loss compared to a 220v circuit. If severe enough, voltage loss can in turn effect the performance of a motor. It's variable to a large degree, in part because every circuit is somewhat unique, so what's true in some cases isn't necessarily true in all cases. The culprits of voltage loss are often things like using long runs of wire, inadequate wire gauge, old wire, improper metallurgy, long extension cords, multiple junctions, or other devices running on the same circuit…there could be other reasons too. The larger the amp draw of a given motor, the more likely that voltage loss will occur in the circuit…..typically motors of 2hp or more are best run on a 220v circuit. It's important to note that most motors have a nominal amp draw indicated on the motor plate, but the actual momentary amp draw can be significantly higher at startup, heavy load, stalling, etc. If significant voltage loss occurs, it can cause a motor to be sluggish, slow to power up, and slow to recover from load. It can also cause excess heat, which can lead to shorter service life, or even premature permanent damage. A 220v circuit is less likely to approach the limits of it's supply capacity because the amperage delivery is halved, so is less likely to incur voltage loss. The ability of an adequate circuit to supply full power to the motor coils allows the saw to run to it's full potential…this often gets misinterpreted as 220v making the motor more powerful….it's not, it's just no longer being starved for power. Once the voltage loss issue is solved, the end result is that your saw's motor should be more responsive…faster startup, faster recovery, giving the perception of less lugging, etc. It can be argued that an adequate 120v circuit with large enough gauge wire that only supplies electricity to your saw would work just as well, but the concept of sharing the work load across two leads makes sense as opposed to one lead carrying twice the current. If you have 220v readily available, and your saw can run on 220v, there's little downside to making that switch. If you don't have 220v, and you have absolutely no issues running your 120v saw on a 120v circuit, there's little reason to pursue it. However, if your 120v saw currently lugs easily, comes up to speed slowly, recovers slowly, dims lights, etc., it could be worth putting in a 220v line.

Some Basics of Buying a Saw -

For performance and stability, large and heavy is a good thing, operating room and support are good, strong and powerful are good, and rigid and precise are all good things. From that perspective, in most applications metal is preferred to plastic …cast iron is preferred to steel, steel is preferred to aluminum, aluminum is preferred to plastic, stronger plastics are preferred to more brittle plastics, etc. It's subjective to some degree, but you get the gist of the strength of materials game.

Since alignment is critical to good performance, the ability to adjust the blade to the miter slots, and the fence to the blade are also good. When you approach a table saw in a store, try to imagine whether or not the saw would be stable when you push a piece of heavier material across the blade. Is there enough operating room in front of the blade for you to get the work piece settled before it contacts the blade? Push a little on the front of the saw…if it moves easily, it'll move when you're cutting if you don't take precautions to anchor it down. It's hard to know how powerful a saw will feel when cutting until you've used it… there's a lot more to how easily a saw cuts than it's horsepower rating, but if the blade isn't cutting efficiently while your pushing the material, it'll ultimately translate to pushing on the saw, so it has to be stable. Blade selection and alignment are key factors in how easily and accurately any saw cuts. Horsepower ratings can be misleading or vague, but you can at least check the stated nominal amperage on the motor plate, manual, or specs. "Amp" draw is an indication of how much power it'll draw from the electrical circuit, and is a better indicator of how much power it'll produce during operation than HP ratings….it's not an ideal rating system, just better…especially with universal motors. If you're unfamiliar with the difference between a universal motor and an induction motor, think in terms of a running circular saw vs a ceiling fan…circular saws have universal motors, while fans have induction motors. Universal motors tend to be substantially louder than induction motors….quiet is usually good too!. There are many other variables involved with the saw's perceived power, but that at least gives you a leg up on whatever wishful number the marketing wizards have printed on the front of the saw. They've earned our suspicion, so take their advertising claims lightly! If it plugs into a standard 120v outlet, it's not mathematically feasible for the circuit to safely supply enough amperage for the motor to produce more than 2hp for long enough to matter. Any motor that's larger than a true 2hp is best run on a 240v (aka 220v) circuit.

The fence is a critical part of the cutting operation during rip cuts, so check it out thoroughly….it should have easy adjustments for horizontal and vertical alignment, and should clamp down firmly on the fence rail, or should at least have adjustments for the clamping pressure. If it sticks a little on the rail, don't worry… a little lubrication in the right location should help it gliding nicely (never lubricate where the fence clamps against the rail though). Stock miter gauges are notoriously poor, but with an aftermarket miter gauge or crosscut sled, are easier to compensate for than a bad fence. Check to see if the miter slots are a standard 3/4" width. If not, then you're on your own for accessories that fit the miter slot. Keep in mind that many store displays are horribly adjusted and poorly setup. Don't misjudge a saw because of the display setup…if it's adjustable or loose, that can usually be rectified with proper setup.

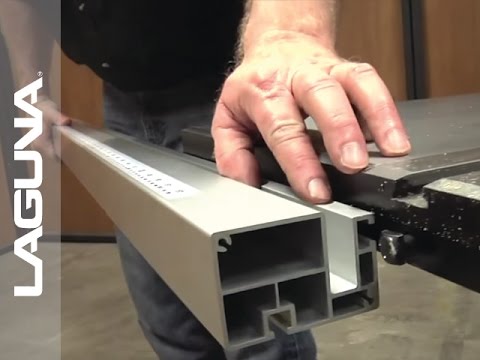

The Biesemeyer Commercial "T-square fence" is the most heavily copied fence in the industry, and is the most common style of fence found on industrial cabinet saws. It's heavy welded steel construction, ease of setup, ease of use, accuracy, and goof proof design changed the industry standard for the better. You'll find heavy duty examples from Biesemeyer (now owned by Delta), Shop Fox Classic, Jet Xacta II, Powermatic Accufence, HTC, General T-fence, Steel City, Saw Stop T-Glide, and more. Vega also makes an excellent fence that has some similarities but uses a different approach. There are also some lighter duty versions of steel t-fences….Delta T2 (and now the T3), Jet Proshop, GI, Grizzly, Steel City, Saw Stop, and others. There are some key differences in steel thickness and construction, so make a point of examining a heavy duty t-fence before settling on a lighter duty version. Note that some of the lighter duty t-square fences use bolts to mount the fence tube to the t-square head vs welds. Either may be suitable for your needs, but it's worth investigating in advance if possible. It's more common to find the lighter duty versions on contractor saws and hybrids, but all can be adapted to nearly any style of full size stationary saw, and many are available as aftermarket accessories. The Incra ultra-precision fence is arguably among the most precise and repeatable aftermarket fences available, though it's worth noting that it takes up some extra space on the right side of the saw.

Lighter Duty T-square fences:

![Image]()

![Image]()

Heavy Duty T-square fences:

![Image]()

![Image]()

You'll also discover that some saws have table mounted trunnions, while virtually all modern industrial cabinet saws and some contractor/hybrid saws have cabinet mounted trunnions. Cabinet mounted trunnions are generally easier to reach and easier to align. Table mounted trunnions can be more tedious, but it's usually a one time deal and is manageable. It's also worth noting that many of the hybrid and lighter duty cabinet saws have gone to cabinet mounted trunnion brackets that bolt through the middle of the front and rear frame struts, as opposed to the large corner to corner mounts of typical industrial cabinet saws. This newer format can actually look a great deal like table mounted trunnions, but technically they're not table mounted. It's a step in the right direction vs table mounted trunnions, but don't confuse the marketing advantage of claiming "cabinet mounted trunnions" with the performance advantage of the heavy duty version generally found on true industrial cabinet saws. There are examples of both types in the pics above…specifically the Laguna Fusion shows cabinet mounted trunnions that connect to the frame struts (very similar designs are in the Jet Proshop and Baleigh hybrids, and a beefier version in the Saw Stop PCS). Pics of the PM2000 and Griz G1023RL show the bigger trunnion brackets used in industrial cabinet saws like the Jet Xacta, Saw Stop ICS, G0690, Laguna Platinum, Craftex CX200, and Baleigh 3hp+ cabine saws.

Motor Power -

The question of adequate motor power for a woodworking saw comes up fairly often. In general, a well setup saw with a 1 to 1.5hp motor that's equipped with a proper blade for the task is sufficient, though seldom is more power undesirable. As mentioned earlier, a tad under 2hp is about the most you can expect a standard 120v circuit to support. Larger motors will draw more amperage than a standard 120v can safely supply, so are typically best run on a 240v circuit (aka 220v). Will you notice a difference by going with 3hp or more? Absolutely. The jump from a motor on a typical contractor saw or hybrid saw to an industrial 3hp motor represents a horsepower increase of between 70% and 100%, or greater. Would you notice a difference in your family sedan if you replaced the 175hp motor with a 300hp motor? You bet! If you have 220v available, or it can be easily added, it's worth some consideration, but it's not an essential for the majority of hobbyists.

The Great Debate - Right Tilt or Left Tilt?

Virtually all modern table saws have the ability to tilt the blade for bevel cuts. Some tilt towards the right, some tilt towards the left. There are pros and cons to both which many feel are minor concerns, and it really boils down to a matter of preference. Right tilt bevels toward the fence on a standard bevel cut, which is considered less safe than if it beveled away from the fence. You can move the fence to the left of the blade for safer bevel cuts, but that makes it a non-standard operation, which is still not quite as safe as a bevel cut on a left tilt saw. On Left tilt saws the blade bevels away from the fence with the fence on the right of the blade (standard location), which is considered safer.

The downside of a left tilt saw is that any changes in blade thickness will skew the zero reference on the tape measure because the left side of the blade registers on the right side of the flange (the same direction as the tape measure reads). This can be adjusted by recalibrating the cursor, always using blades of the same thickness, using shims as spacers, or just measuring by hand. Blade thickness changes make no difference with a right tilt saw because the right side of the blade registers against the left side of the flange, so changes in blade thickness don't impact the tape measure. Here's another difference that will also be a matter of preference - the arbor nut on a right tilt saw gets applied from the left side of the blade and uses a reverse thread orientation, which is typically done with your left hand. The arbor nut on a left tilt saw goes on from the right side (easy for right handers) and uses a normal thread orientation.

What to Buy?

Which saw to get is a personal decision that we all face. A table saw is the heart and soul of the majority of wood shops. Each of us has different criteria for a saw, so make your decision based on your situation. Price is often a big consideration, as is size. The old adage, "buy the best saw you can afford" rings true. If space and price allows, a bigger saw would be my recommendation….more power, more capacity, and more stability is seldom a bad thing. The performance advantages of the larger full size saws are hard to argue, but many of the better portable jobsite saws and some of the compact saws are capable of producing accurate cuts. If a smaller saw is all there's room for, or if you need to move the saw from location to location, a larger saw may simply be unfeasible.

If budget is the limiting factor, look to a good used saw instead of a new portable or bench saw….Craigslist, Ebay, and the used classifieds on woodworking sites can often yield an excellent saw for a reasonable cost. Older full size contractor saws are plentiful in the used market….it's very common to see a used Ridgid or Craftsman contractor saw in the $100-$200 that could be ready to go with a new blade and very little effort. The fences on the old Craftsman saws were pretty suspect, but fence upgrades can be added at a later time as funds allow. Thanks to the wonders of the Sawstop flesh sensing technology, there are many excellent full size saws available due to people upgrading to the new technology. This is a great time to find a good used industrial cabinet saw at a good price….just beware that you'll need 240v operation if the motor is more than 2hp.

New full size saws tend to start just north of $500. Sale prices and coupons can drop the price further. I've read of several cases where a store has honored a Harbor Freight 20% competitor's coupon, which can bring entry level full size saws like the Ridgid R4512, Delta 36-725, or Craftsman 21833 down in the $425-$450 range. If you've got 240v, you just might find a great deal on a used cabinet saw for within that same budget. You'll have to decide if you'd rather have a new saw with warranty and modern features like a riving knife, or if you'd rather buy more beef under the hood. New cabinet saws tend to start near $1300….a new Grizzly G1023RL 3hp cabinet saw is currently available for around $1400 shipped, and enjoys a very solid reputation…..that's pretty close in price to several of the better hybrid saws, and offers much more substantial construction. Regardless which type you end up with, the end performance is largely determined by proper setup and good blade selection, so take your time with the alignment and setup, and buy a quality blade. Good blades tend to start right around $30….if that's all that's in your blade budget, I'd buy one decent general purpose blade as opposed to a two-pack of cheaper blades, but it really depends on what you plan to do.

Making Sense of Table Saw Classifications -

Buying a new table saw can be a little confusing to an inexperienced buyer. The models, brands, manufacturers, and types of saws are in a constant state of change. What was true just a few years ago may no longer apply, so it can be difficult to get reliable information even from seasoned veterans if they haven't been keeping up on the trends. Even seasoned veterans may be surprised at how rapidly the marketplace changes. To help simplify your purchase, here's one man's view of the table saw marketplace in the USA (and some Canadian choices) in 2012. Opinions vary widely about which saws are best, and the classifications are more blurred than ever. Because many saws roll off the same assembly lines from the same plant, but sport different name plates and color schemes, in my opinion it's better to focus more on the type of saw that's most suitable for your needs than what brand name to buy. Don't dismiss a full size saw because of your impressions of a portable saw of the same brand, or vice-versa….there's often very little correlation between them. A step up in class from a lesser brand is still a step up in class, and is likely a better choice than a downgrade in class from a more prominent brand. This article will help explain some of the basic features and differences between types of 10" table saws that are commonly found in the US.

The vast majority of table saws available in today's market can be divided into two major categories - portable and stationary, with varying sub-classifications for each. This article will focus only on saws with standard 5/8" arbors that will accept standard 10" saw blades.

Portable Saws:

Portable saws include 3 subgroups - the entry level bench top models, compact saws, and portable jobsite saws. They're primarily designed to be light and mobile. The vast majority have universals motors, most of which are direct drive, and run on standard 120v residential circuits. Those that are belt driven tend to use a light duty cogged vacuum cleaner style drive belt. Universal motors tend to be considerably louder than induction motors, and have less torque, so they tend to rely on higher RPM to get the cutting done. Most have motors that are rated between 10 and 15 amps, and typically generate between 1 and 2 usable horsepower. Claims of greater horsepower than that are misleading…if it plugs into a standard home outlet, it's not more than 2hp (at least not for very long). Many are also available with a variety of lifts and leg stands….which is where our first point of confusion shows up. For the sake of simplicity, let's assume that a portable benchtop or jobsite saw on a leg stand is still a portable saw.

Bench top saws tend to be small, light, inexpensive, and aimed mainly at the entry level casual home owner. There are several models readily available typically costing in the $100-$200 range, or less, from brands like Skil, Black & Decker (Firestorm), Craftsman, Tradesman, Ryobi, Hitachi, Task Force, Rockwell, Central Machinery, Pro Tech, Cummins, Delta, Jet, and others. The same saws mounted on a leg stand can run upwards of $300. To keep weight and cost down, bench top models tend to feature materials and designs that aren't overly robust. Most feature plastic or very lightweight metal housings, plastic or cheap pot metal gears and mechanisms, aluminum or composite tops, very small tables, and poorly designed fences that are awkward and difficult to get accurate results with. Many of these saws are made to "look" the part of higher grade jobsite saw to the uninformed, but the similarities don't go very deep….most are little more than a circular saw mounted upside down in a plastic housing. Many are no more than 17" deep, leaving very little room to operate in front of the blade, which can make safe accurate cuts more difficult. Most don't feature standard size miter slots, or don't accommodate the use of common aftermarket accessories or parts from other saws. Operating space is very limited, and the lighter weight makes them less stable during operation (many weigh in the range of 50#). They'll cut wood and other materials, but can be difficult and frustrating to use. It's often not feasible to repair them in the event of a mechanical or electrical failure. Bench top saws of this type tend to cost less upfront, but generally represent a very poor value overall due to their poor resale value, poor reliability, and mediocre performance. Sometimes it's prudent to save a little longer and spend a little more to spare yourself the trouble and wasted money. Buying a better quality used saw is often a better option if the right deal comes along. In some cases your needs would be better met by a basic circular saw with a good blade, and a decent straight edge used as a guide.

Portable jobsite saws represent a more ruggedly built class of portable saws. These are the type of saws that most carpenters, contractors, and tradesman use on the jobsite… which might explain why they're often incorrectly referred to as "contractor saws". They're still small, light, and portable, and retain many of the disadvantages inherent to a smaller saw, but are made more ruggedly and are generally more accurate than the entry level bench top saws. Most still have direct drive universal motors, and lightweight construction compared to a full size stationary saw, but the motors, gears, and underpinnings are made to hold up better to the rigors and demands of a construction site than most bench top models. Most have reasonably powerful 15 amp motors, many have standard ¾" miter slots, decent fences, better alignment adjustments, extension tables, ripping capacities up to 24", and are available with a variety of clever foldup or rollaway leg stands. There are popular and reasonably capable models from companies like Bosch, DeWalt, Ridgid, Porter Cable, Makita, Jet, Craftsman, Hitachi, and Ryobi, among others. Prices tend to be in the $300-$600 range, and many are capable of suitable accuracy for furniture making in the hands of a skilled woodworker. All have their fans, but the Bosch, DeWalt, and Ridgid are the perennial top dogs in this class. These saws have modern riving knives, some have dust collection ports, and are an excellent option if you need to move the saw easily from location to location, or need to easily stow them out of the way. However, they still don't offer the sheer size, mass, and performance benefits of a full size stationary saw.

Compact saws are a slightly larger class of saw than the entry level bench models, but are still lighter, smaller, less expensive, and more portable than full size stationary saws. They're often still considered bench top saws, and still tend to retain direct drive universal motors, and less rugged overall construction, though some do feature a cogged vacuum cleaner style belts, and most will have some sort of a leg stand. Some even feature cast iron tops, and can look remarkably similar to a full size contractor saw from a glance, though the table area is smaller and the construction is significant lighter duty.

Stationary Saws:

Stationary saws include the main categories of contractor saws, hybrid saws, and cabinet saws. They're considerably heavier, larger, and more robust than the class of portable saws. Though inherently less portable, any of these saws can be placed on a mobile base and rolled easily around the shop. Some even have built in mobile bases. These are typically full size saws with cast iron tops and belt drive induction motors, but there are examples that offer solid granite tops instead of cast iron, and even some with aluminum tops. The vast majority have standard ¾" miter slots on each side of the blade. A standard full size top tends to have a main table that's approximately 27" deep x 20" wide, with 10" to 12" extension wings made of steel or cast iron on each side for a total width of roughly 40" to 44". There are exceptions and variations across the board, with some having deeper tables, extra wide extension tables, router tables, outfeed tables, longer fence rails, etc. In a standard configuration, these saws all tend to take up about the same amount of floor space. However, the older style contractor saws with the motor hanging off the back take up an additional 12" to 13" for the motor. It's a common misconception that cabinet saws take up more space. In their stock configuration, the cabinet saws actually have a smaller footprint than a traditional older style contractor saw with an outboard motor. It isn't until you add longer rails for more rip capacity that the area increases for any saw in this class. The misconception arises because it's simply more common to find a cabinet saw with wider rip capacity than it is a contractor saw or hybrid with a similar setup.

This is the class of saw that most hobbyists, smaller professional shops, and schools will gravitate toward. Many will run on a standard single phase 20 amp 120v residential circuit, while others require a 240v circuit (2 horsepower and up). Some that are used in industrial settings will operate on 480v 3-phase circuits. These saws tend to have good adjustability and can be made to be very accurate. They're large and stable enough to handle most sheet goods, powerful enough to cut most lumber to near full blade height if aligned well and fitted with a proper blade. They have ample table space and good operating room in front of the blade, making them inherently safer to use. There are many good fence options available, most will accept standard accessories, and are built to last for decades with basic maintenance. They're also usually easier, and cheaper to fix in the event of a failure. Many of the motors are on a standard NEMA 56 frame, so off-the-shelf replacement and upgrade motors are readily available. Many parts like the wings, fences, and miter gauges are directly interchangeable with all three classes of stationary saws, or can be easily modified to fit, so upgrades for basic features are often possible, making stationary saws a good long term investment.

Compare the significant difference in the size of the "landing zone" in front of the blade between a portable and a full size stationary saw. That extra space not only keeps hands farther away from the blade, it also gives the work piece more time to settle and register against the table and fence providing better accuracy:

.

Contractor Saws:

For years, the most common full size stationary saw has been the traditional contractor saw with a belt drive outboard induction motor hanging out the back of the saw. These were developed over 60 years ago as a jobsite alternative to heavier cabinet saws, and were used by carpenters and craftsman in the field. These were the true original "contractor saws". The motor was designed to be easily removed to improve portability, were initially typically ½ to 1 horsepower, and could run on standard residential 110v circuits (now known as 120v). The belt driven arbor was suspended between two trunnion brackets that mounted to the table top. This design was lighter and cheaper to manufacture, but were a bit difficult to reach and made alignment more of a chore. Over time, the horsepower increased to an average of 1hp to 2hp…about the maximum horsepower rating that a motor that will run on a standard 120v circuit can achieve. Though more portable than a 500# industrial cabinet saw, at 200# to 300#, a traditional contractor saw was still very heavy to be moved regularly from one location to another, but were capable, accurate, and reliable. In addition to being heavy, the location of the outboard motor had some disadvantages….the motor took up more space, required a longer belt (additional vibration), posed a lifting hazard when the motor was tilted, put additional stresses on the alignment when tilted, and generally had poor dust collection. This design remained relatively unchanged for several decades, with most improvements focused on the precision of the fences, safety features like guards and splitters, standardization of table size and miter slots. As smaller, more portable saws evolved, contractor saws became largely relegated to use as permanently located stationary shop saws. They also gained appeal as home shop saws for hobbyists and smaller professional shops because they were more affordable than cabinet saws, yet offered good performance for fine woodworking. In their new role as a stationary saw, easy access for motor removal was no longer necessary, so the location of the motor eventually found its way inside the enclosure, which resolved the nuisance issues of the outboard location. There are very few traditional contractor saws with outboard motors still available new in the marketplace these days. The Saw Stop contractor saw is the sole survivor of currently manufactured consumer table saws with outboard motors. The Powermatic PM64a is still available, but those are all new old stock (NOS)….you may also find some NOS GI and Delta contractor saws at smaller specialty tool stores, but new models haven't been manufactured for a while.

.

Hybrid Saws:

Most of today's contractor saws feature an inboard belt drive induction motor, as well as an updated splitter known as a riving knife, which raises, lowers, and tilts in unison with the blade as opposed to being fixed in place, or just tilting with the blade as was the case with a traditional splitter. Because the riving knife is less cumbersome, and less likely to be in the way, it's more likely to be in place to do its job. Due to the inboard location of the motor, today's contractor saws are sometimes referred to as hybrid saws, which are a really a cross between a contractor saw and an industrial cabinet saw. One aspect of the older style traditional contractor saws that remains are the open leg or splayed leg enclosures.

There are also several hybrid models that sport full enclosures as opposed to an open or splayed leg stand found on the modern hybrid style contractor saws. Some folks refer to these as cabinet saws, but it's my opinion that it's an oversimplification of the facts. Some savvy marketers promote the confusion by calling their hybrid saws with full enclosures a "cabinet saw". Most of these models still feature table mounted trunnions with similar duty ratings as a contractor saw, but some do offer cabinet mounted trunnions. These are just some of the issues that complicate trying to categorize saw types. I suppose the nomenclature really boils down to semantics, but make no mistake about it….a hybrid saw with a full enclosure, whether it uses table mounted or cabinet mounted trunnions, does not have the same power, mass, duty rating, or robust design as a true industrial style cabinet saw. Modern updated hybrid style contractor saws and hybrid saws are available from companies like Jet, Powermatic, Shop Fox, Ridgid, Craftsman, Delta, Master Force, Craftex, King, Grizzly, Porter Cable, Baleigh, Steel City, General International, Woodtek, Saw Stop, Rikon, Dayton, and others starting at about $525 going up over $2500 for a well appointed Saw Stop model.

.

.

Industrial Style Cabinet Saws:

Industrial cabinet saws are at the top of the food chain in this article, though there are high volume modern specialty saws available commercially that won't be covered here. Industrial cabinet saws are the true workhorses found in many cabinet shops, factory shops, commercial shops, schools, and serious hobby shops across the country. The vast majority retain the same standard table dimensions mentioned above, so from the top, they can look a great deal like a contractor saw or a hybrid saw. Most can even accept many of the same standard accessories, but aside from that, the similarities under the hood end there. The underpinnings of an industrial cabinet saw are much heavier duty than those of any other type of table saw mentioned here, making them very accurate, heavy, stable, and durable. The fences tend to be precise and robust, often made of heavy welded steel. The mechanisms and adjustments tend to operate as they should, making them a pleasure to use. They also tend to have more horsepower, with most falling into the 3hp to 5hp range, and requiring 240v electrical circuits. There are few standard cuts that these saws struggle with. Most come with a high quality fence, and solid cast iron wings. All of the modern designs that I'm aware of feature cabinet mounted trunnions, which are easier to align than table mounted trunnions. Most have the large yoke style trunnions that span from corner to corner of the cabinet. Weighing in excess of 500# makes these saws very stable, but not very portable. However, when placed on a good mobile base, most can be easily wheeled around the shop. The venerable Delta Unisaw was one of the earliest, most popular, and most copied of this type of saw. There are now excellent examples from Delta, Powermatic, Grizzly, Shop Fox, Jet, Saw Stop, Steel City, Rikon, Laguna, Woodtek, General, General International, Baleigh, Craftex, Oliver, and King Industrial, among others. Starting prices tend to be in the $1300 range, topping out over $4000. Some would consider a saw of this caliber overkill for a hobbyist, but they can be fairly affordable considering what you get for $1300 to $1500 relative to one of the better 120v hybrid saws.

Switching a 120v motor to 220v (aka 240v):

Some motors can be run on either 120v or 220v. The benefits of switching to 220v is one of most debated and error ridden discussions you'll find on the internet. My limited knowledge of electricity isn't sufficient to settle all aspects of those debates here, but here's a brief layman's explanation that I hope will at least provide a fighting chance at understanding some of the underlying controversy and benefits involved. (someone please correct me if I've written any glaring errors).

The types of motors used on most saws with induction motors have two sets of coils….they either run in series or in parallel with each other, depending on whether they're wired for 120v or 220v. Each coil sees roughly the same amperage whether run on 120v or 220v, so in theory, there should be no difference in how the motor performs. What changes is the amount of amperage carried by the supply leg or legs of the circuit. The motor is essentially the same, but the supply lines are not, which I think is a key point that often gets overlooked in this debate. 220v circuits supply amperage from two opposite hot supply lines, that each carry half the required current to the motor coils. 120v circuits supply amperage from one hot leg, which supplies all of the required current, which can cause more heat and requires heavier gauge wire. Even though head room is designed into all good electrical circuits, 120v circuits will inherently run closer to 100% of their capacity than a 220v circuit, which can cause some loss of efficiency and voltage loss compared to a 220v circuit. If severe enough, voltage loss can in turn effect the performance of a motor. It's variable to a large degree, in part because every circuit is somewhat unique, so what's true in some cases isn't necessarily true in all cases. The culprits of voltage loss are often things like using long runs of wire, inadequate wire gauge, old wire, improper metallurgy, long extension cords, multiple junctions, or other devices running on the same circuit…there could be other reasons too. The larger the amp draw of a given motor, the more likely that voltage loss will occur in the circuit…..typically motors of 2hp or more are best run on a 220v circuit. It's important to note that most motors have a nominal amp draw indicated on the motor plate, but the actual momentary amp draw can be significantly higher at startup, heavy load, stalling, etc. If significant voltage loss occurs, it can cause a motor to be sluggish, slow to power up, and slow to recover from load. It can also cause excess heat, which can lead to shorter service life, or even premature permanent damage. A 220v circuit is less likely to approach the limits of it's supply capacity because the amperage delivery is halved, so is less likely to incur voltage loss. The ability of an adequate circuit to supply full power to the motor coils allows the saw to run to it's full potential…this often gets misinterpreted as 220v making the motor more powerful….it's not, it's just no longer being starved for power. Once the voltage loss issue is solved, the end result is that your saw's motor should be more responsive…faster startup, faster recovery, giving the perception of less lugging, etc. It can be argued that an adequate 120v circuit with large enough gauge wire that only supplies electricity to your saw would work just as well, but the concept of sharing the work load across two leads makes sense as opposed to one lead carrying twice the current. If you have 220v readily available, and your saw can run on 220v, there's little downside to making that switch. If you don't have 220v, and you have absolutely no issues running your 120v saw on a 120v circuit, there's little reason to pursue it. However, if your 120v saw currently lugs easily, comes up to speed slowly, recovers slowly, dims lights, etc., it could be worth putting in a 220v line.

Some Basics of Buying a Saw -

For performance and stability, large and heavy is a good thing, operating room and support are good, strong and powerful are good, and rigid and precise are all good things. From that perspective, in most applications metal is preferred to plastic …cast iron is preferred to steel, steel is preferred to aluminum, aluminum is preferred to plastic, stronger plastics are preferred to more brittle plastics, etc. It's subjective to some degree, but you get the gist of the strength of materials game.

Since alignment is critical to good performance, the ability to adjust the blade to the miter slots, and the fence to the blade are also good. When you approach a table saw in a store, try to imagine whether or not the saw would be stable when you push a piece of heavier material across the blade. Is there enough operating room in front of the blade for you to get the work piece settled before it contacts the blade? Push a little on the front of the saw…if it moves easily, it'll move when you're cutting if you don't take precautions to anchor it down. It's hard to know how powerful a saw will feel when cutting until you've used it… there's a lot more to how easily a saw cuts than it's horsepower rating, but if the blade isn't cutting efficiently while your pushing the material, it'll ultimately translate to pushing on the saw, so it has to be stable. Blade selection and alignment are key factors in how easily and accurately any saw cuts. Horsepower ratings can be misleading or vague, but you can at least check the stated nominal amperage on the motor plate, manual, or specs. "Amp" draw is an indication of how much power it'll draw from the electrical circuit, and is a better indicator of how much power it'll produce during operation than HP ratings….it's not an ideal rating system, just better…especially with universal motors. If you're unfamiliar with the difference between a universal motor and an induction motor, think in terms of a running circular saw vs a ceiling fan…circular saws have universal motors, while fans have induction motors. Universal motors tend to be substantially louder than induction motors….quiet is usually good too!. There are many other variables involved with the saw's perceived power, but that at least gives you a leg up on whatever wishful number the marketing wizards have printed on the front of the saw. They've earned our suspicion, so take their advertising claims lightly! If it plugs into a standard 120v outlet, it's not mathematically feasible for the circuit to safely supply enough amperage for the motor to produce more than 2hp for long enough to matter. Any motor that's larger than a true 2hp is best run on a 240v (aka 220v) circuit.

The fence is a critical part of the cutting operation during rip cuts, so check it out thoroughly….it should have easy adjustments for horizontal and vertical alignment, and should clamp down firmly on the fence rail, or should at least have adjustments for the clamping pressure. If it sticks a little on the rail, don't worry… a little lubrication in the right location should help it gliding nicely (never lubricate where the fence clamps against the rail though). Stock miter gauges are notoriously poor, but with an aftermarket miter gauge or crosscut sled, are easier to compensate for than a bad fence. Check to see if the miter slots are a standard 3/4" width. If not, then you're on your own for accessories that fit the miter slot. Keep in mind that many store displays are horribly adjusted and poorly setup. Don't misjudge a saw because of the display setup…if it's adjustable or loose, that can usually be rectified with proper setup.

The Biesemeyer Commercial "T-square fence" is the most heavily copied fence in the industry, and is the most common style of fence found on industrial cabinet saws. It's heavy welded steel construction, ease of setup, ease of use, accuracy, and goof proof design changed the industry standard for the better. You'll find heavy duty examples from Biesemeyer (now owned by Delta), Shop Fox Classic, Jet Xacta II, Powermatic Accufence, HTC, General T-fence, Steel City, Saw Stop T-Glide, and more. Vega also makes an excellent fence that has some similarities but uses a different approach. There are also some lighter duty versions of steel t-fences….Delta T2 (and now the T3), Jet Proshop, GI, Grizzly, Steel City, Saw Stop, and others. There are some key differences in steel thickness and construction, so make a point of examining a heavy duty t-fence before settling on a lighter duty version. Note that some of the lighter duty t-square fences use bolts to mount the fence tube to the t-square head vs welds. Either may be suitable for your needs, but it's worth investigating in advance if possible. It's more common to find the lighter duty versions on contractor saws and hybrids, but all can be adapted to nearly any style of full size stationary saw, and many are available as aftermarket accessories. The Incra ultra-precision fence is arguably among the most precise and repeatable aftermarket fences available, though it's worth noting that it takes up some extra space on the right side of the saw.

Lighter Duty T-square fences:

Heavy Duty T-square fences:

You'll also discover that some saws have table mounted trunnions, while virtually all modern industrial cabinet saws and some contractor/hybrid saws have cabinet mounted trunnions. Cabinet mounted trunnions are generally easier to reach and easier to align. Table mounted trunnions can be more tedious, but it's usually a one time deal and is manageable. It's also worth noting that many of the hybrid and lighter duty cabinet saws have gone to cabinet mounted trunnion brackets that bolt through the middle of the front and rear frame struts, as opposed to the large corner to corner mounts of typical industrial cabinet saws. This newer format can actually look a great deal like table mounted trunnions, but technically they're not table mounted. It's a step in the right direction vs table mounted trunnions, but don't confuse the marketing advantage of claiming "cabinet mounted trunnions" with the performance advantage of the heavy duty version generally found on true industrial cabinet saws. There are examples of both types in the pics above…specifically the Laguna Fusion shows cabinet mounted trunnions that connect to the frame struts (very similar designs are in the Jet Proshop and Baleigh hybrids, and a beefier version in the Saw Stop PCS). Pics of the PM2000 and Griz G1023RL show the bigger trunnion brackets used in industrial cabinet saws like the Jet Xacta, Saw Stop ICS, G0690, Laguna Platinum, Craftex CX200, and Baleigh 3hp+ cabine saws.

Motor Power -

The question of adequate motor power for a woodworking saw comes up fairly often. In general, a well setup saw with a 1 to 1.5hp motor that's equipped with a proper blade for the task is sufficient, though seldom is more power undesirable. As mentioned earlier, a tad under 2hp is about the most you can expect a standard 120v circuit to support. Larger motors will draw more amperage than a standard 120v can safely supply, so are typically best run on a 240v circuit (aka 220v). Will you notice a difference by going with 3hp or more? Absolutely. The jump from a motor on a typical contractor saw or hybrid saw to an industrial 3hp motor represents a horsepower increase of between 70% and 100%, or greater. Would you notice a difference in your family sedan if you replaced the 175hp motor with a 300hp motor? You bet! If you have 220v available, or it can be easily added, it's worth some consideration, but it's not an essential for the majority of hobbyists.

The Great Debate - Right Tilt or Left Tilt?

Virtually all modern table saws have the ability to tilt the blade for bevel cuts. Some tilt towards the right, some tilt towards the left. There are pros and cons to both which many feel are minor concerns, and it really boils down to a matter of preference. Right tilt bevels toward the fence on a standard bevel cut, which is considered less safe than if it beveled away from the fence. You can move the fence to the left of the blade for safer bevel cuts, but that makes it a non-standard operation, which is still not quite as safe as a bevel cut on a left tilt saw. On Left tilt saws the blade bevels away from the fence with the fence on the right of the blade (standard location), which is considered safer.

The downside of a left tilt saw is that any changes in blade thickness will skew the zero reference on the tape measure because the left side of the blade registers on the right side of the flange (the same direction as the tape measure reads). This can be adjusted by recalibrating the cursor, always using blades of the same thickness, using shims as spacers, or just measuring by hand. Blade thickness changes make no difference with a right tilt saw because the right side of the blade registers against the left side of the flange, so changes in blade thickness don't impact the tape measure. Here's another difference that will also be a matter of preference - the arbor nut on a right tilt saw gets applied from the left side of the blade and uses a reverse thread orientation, which is typically done with your left hand. The arbor nut on a left tilt saw goes on from the right side (easy for right handers) and uses a normal thread orientation.

What to Buy?

Which saw to get is a personal decision that we all face. A table saw is the heart and soul of the majority of wood shops. Each of us has different criteria for a saw, so make your decision based on your situation. Price is often a big consideration, as is size. The old adage, "buy the best saw you can afford" rings true. If space and price allows, a bigger saw would be my recommendation….more power, more capacity, and more stability is seldom a bad thing. The performance advantages of the larger full size saws are hard to argue, but many of the better portable jobsite saws and some of the compact saws are capable of producing accurate cuts. If a smaller saw is all there's room for, or if you need to move the saw from location to location, a larger saw may simply be unfeasible.

If budget is the limiting factor, look to a good used saw instead of a new portable or bench saw….Craigslist, Ebay, and the used classifieds on woodworking sites can often yield an excellent saw for a reasonable cost. Older full size contractor saws are plentiful in the used market….it's very common to see a used Ridgid or Craftsman contractor saw in the $100-$200 that could be ready to go with a new blade and very little effort. The fences on the old Craftsman saws were pretty suspect, but fence upgrades can be added at a later time as funds allow. Thanks to the wonders of the Sawstop flesh sensing technology, there are many excellent full size saws available due to people upgrading to the new technology. This is a great time to find a good used industrial cabinet saw at a good price….just beware that you'll need 240v operation if the motor is more than 2hp.

New full size saws tend to start just north of $500. Sale prices and coupons can drop the price further. I've read of several cases where a store has honored a Harbor Freight 20% competitor's coupon, which can bring entry level full size saws like the Ridgid R4512, Delta 36-725, or Craftsman 21833 down in the $425-$450 range. If you've got 240v, you just might find a great deal on a used cabinet saw for within that same budget. You'll have to decide if you'd rather have a new saw with warranty and modern features like a riving knife, or if you'd rather buy more beef under the hood. New cabinet saws tend to start near $1300….a new Grizzly G1023RL 3hp cabinet saw is currently available for around $1400 shipped, and enjoys a very solid reputation…..that's pretty close in price to several of the better hybrid saws, and offers much more substantial construction. Regardless which type you end up with, the end performance is largely determined by proper setup and good blade selection, so take your time with the alignment and setup, and buy a quality blade. Good blades tend to start right around $30….if that's all that's in your blade budget, I'd buy one decent general purpose blade as opposed to a two-pack of cheaper blades, but it really depends on what you plan to do.